Author:

Knut Wimberger

Short summary:

While society stigmatizes manual work, during childhood it is instead crucial to create vivid memories and to teach long lasting practical lessons we will need in our daily life thanks to the educational value of physical activities. Like picking chestnuts from the ground.

The Nature Journal is a personal notebook that all participants in Green Steps activities keep updated to put on paper their experiences and memories in Nature. It can be used to stick with glue leaves and flowers, write down the names of plants, or just draw what you have seen that day.

At Green Steps, we all have a passion for Nature. Nature Journal is the personal digital notebook our team members are sharing with you.

knut wimberger - Green steps co-founder & ceo global services

(austria)

11/10/2020

Is it our connection to the planet or to people which makes us arrive in a place? I don’t know for good, but without a doubt, as we grow older it takes longer to connect to people, while nature remains unchanged and open to be explored.

Last Friday I picked up our son from his new school, a building with a delightful fin de siècle appearance. It was a sunny day, far too warm for mid-October. I felt an immediate pull to stay in the school garden after a busy morning in the office to absorb this autumn afternoon. Isak, my son, asked me to play soccer with him and one thing led to another.

I recalled the parents’ group for garden maintenance asking to bring order into the tool shed. Opening it, I found a moist dump that hadn’t been accessed in a while and decided to take out into the sunlight everything I found. Another boy from the same school joined, and the three of us first separated tools from trash, and then put everything back in neat order.

We kept the rakes, a shovel, and three plastic crates outside to collect all the chestnuts covering the gravel in front of the school. Somehow, I wanted to do a fall clearance in the garden and thus motivated the boys to fill the wheelbarrow with leaves and chestnut peels and bring everything to the compost heap in one far corner of the garden.

Holding chestnuts in my hands, picking them from the ground, and throwing one by one into the crates: I ended up recalling what probably was my first conscious encounter with nature. It’s strange how kinesthetic and tactile impressions find their way into building memories that surprisingly reemerge when engaging in similar activities decades later.

I must have been 12 and it was most likely the year 1988 when Dr. Gusenbauer - I think that was his name - a retired teacher, reverend, and huntsman asked students in our Christian boarding school to collect chestnuts. He explained that he fed them every winter to different species of local wild local animals, including deers and boars, and offered a small amount of cash in exchange for every kilogram.

It wasn’t my interest in nature that got me going, and for sure not a particular passion for gathering chestnuts, but the promise of making some pocket money to buy sweets and other things on my own was tempting enough to spend quite a few afternoons under those trees.

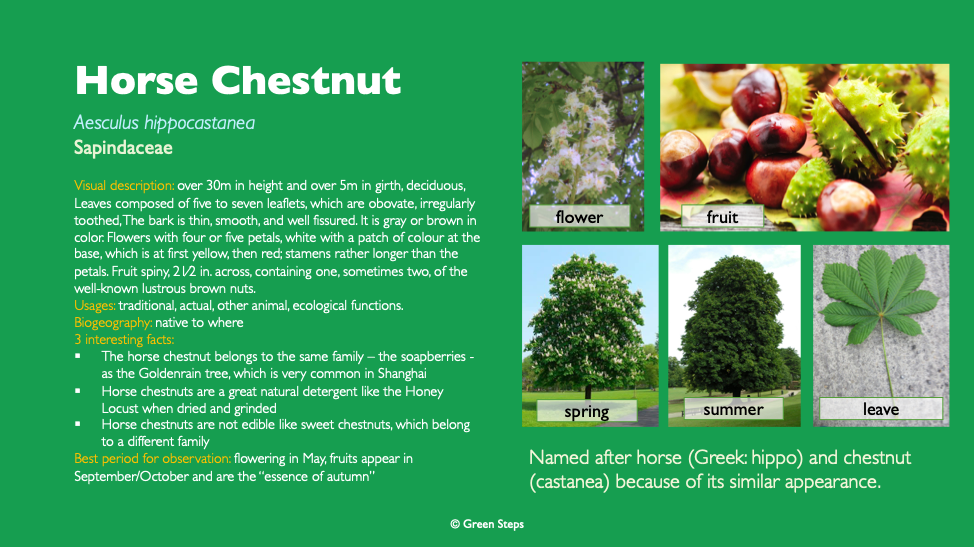

The chestnut tree is with no doubts the European tree most familiar to me. I spent the last 20 years in China, but when I started exploring nature there I had no biological knowledge to fall back on. Nothing but the chestnut tree, whose seasonal change I had observed on my school grounds.

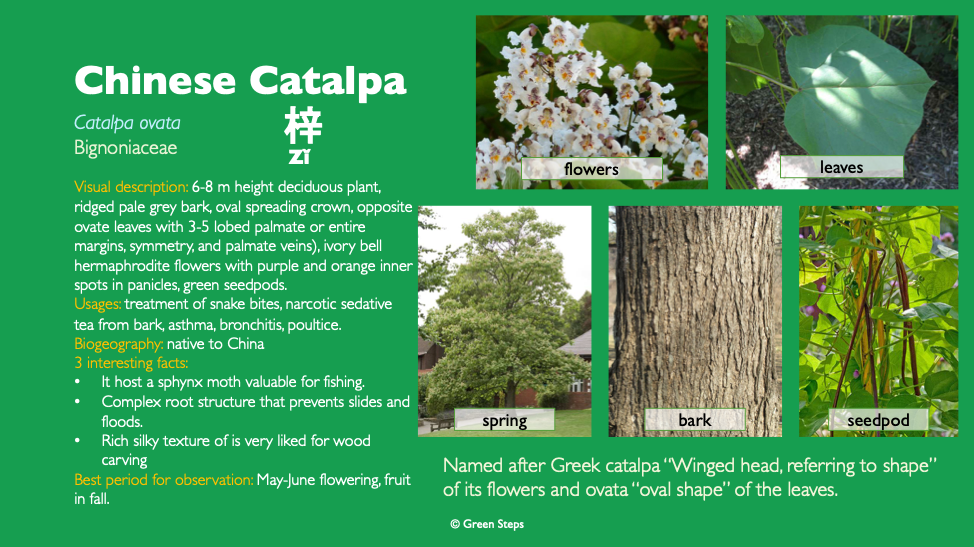

In Shanghai, I should befriend a tree called Catalpa Ovata, which reminded me of the chestnut tree because of its flowers. They bloom in a similar white and are of the same spectacular size and shape. When talking to people about the Catalpa Ovata I would always refer to its similarity with the European horse chestnut. The two are undetachable in my mind.

Looking back at my own childhood and to what got me motivated to explore nature, I doubt that any of the kids sitting in school with our son has whatever incentive to go outdoors and take a sensorial deep dive into nature. I had the promise to earn real money: maybe not much, but enough to gain a slice of independence. Children nowadays have no motivation to engage with the outdoors, if not - maybe - getting better grades. Duh. How boring!

Our affluent society puts such a tremendous emphasis on the acquisition of knowledge, but disregard physical activities and their educational value. Manual work is still stigmatized; to such an extent that in our son’s new school parents share monthly facility cleaning chores to play their offspring free. Why not do it with them, if not let them clean up on their own?

This leads to another memory, probably a common one. It was probably also 1988 when I watched for the first time one of my all-time favorite childhood movies: Karate Kid. You might remember the famous scene where the main character, to his dismay, is “sentenced” to polish for many long hours the car of his newfound master. He will understand only a little while later that the polishing movement is an important gross motor skill in karate defense.

I feel more and more like modern education is deeming all the skills we actually need in our daily lives as worthless, to such an extent that children do not learn anymore how to properly clean and repair facilities, cook meals and do all the other things required to maintain a school as much as a home.

Few people question this development. Schools have turned into ivory towers where quite abstract knowledge is supposed to be learned, but all the practical experiences which create a genuine feeling of self-worth and community have been eradicated and transplanted into another imaginary realm, almost exclusively occupied by immigrants on our labor markets.

Being able to cook for oneself a healthy meal, knowing which herbs can cure what illness: isn’t this a form of self-defense, as well? Assessing most of the industrial junk foods our retailers sell, we have a responsibility to teach our children how to independently get a balanced diet and build a strong immune system. Covid-19 should have made this clearer than ever before.

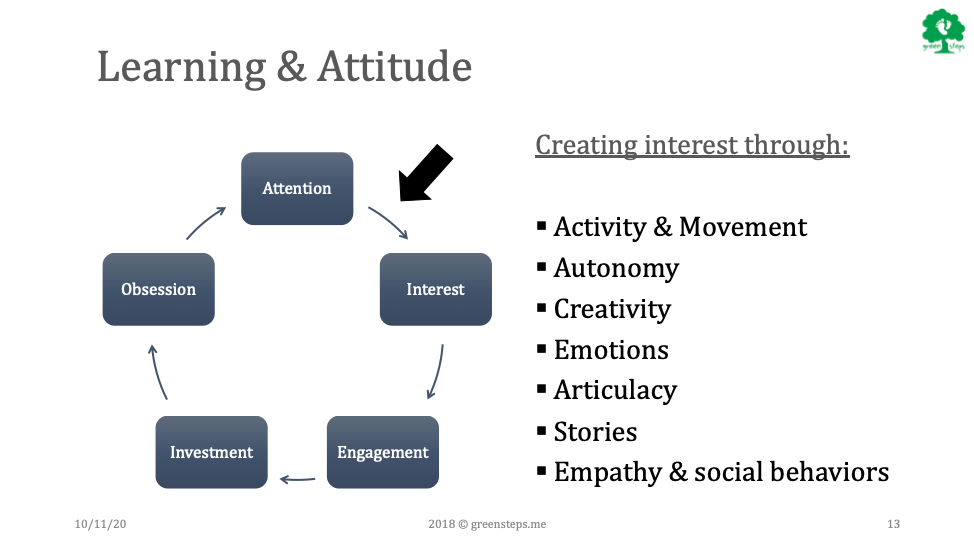

What our industrial education systems and those maintaining them miss, is a crucial point. Practical experiences are a great starting point to get the student’s attention and engagement. For two important reasons:

1, Human being loves collaborative learning, at least to get things started and ignite interest.

2, Practical experiences and kinesthetic learning paves the road for abstract learning and occupations which require higher cognitive functions.

Italian pedagogue Maria Montessori knew about the value of manual learning and therefore designed many Practical Life activities for early childhood which range from pouring water from a pitcher to being able to bind one’s shoelaces. Dale Gausman, founder of the North American Montessori Center writes:

Practical Life activities are often referred to as the heart of Montessori education. In addition to helping children master everyday tasks, the aim of practical life activities is to develop a child’s independence, body control and coordination of movement, concentration, and sense of order.

No matter which Montessori school I have seen, Practical Life is not given the value it should have. Even Dr. Montessori indeed designed Practical Life activities mostly for early childhood, but we need to acknowledge that a highly automated and fully industrialized society of the 21st century exposes the human being to quite a different life than the industrializing society Dr. Montessori built her curriculum upon in Italy’s early 20th century.

There are two reasons for this situation:

1, Most pedagogues do not fully understand what Dr. Montessori meant when she said that: Cognition is born from manual movement. While we educate some children which respond well to abstract intelligence, we neglect the multitude of children which want to respond to the concrete.

2, The designers of modern curricula don’t see the need for an urgent adaptation of our behavioral architecture if we want to avoid a runaway climate crisis. Shifting selected activities in our societies back from machines to man is paramount if we want to keep people and planet sane.

The exercises of practical life are formative activities. They involve inspiration, repetition, and concentration on precise details. They take into account the natural impulses of special periods of childhood. Though for the moment the exercises have no merely practical aims, they are a work of adaptation to the environment. Such adaptation to the environment and efficient functioning therein is the very essence of a useful education.

What formative activities are required to adapt to the changing environment we have to face in the 21st century? Every reader of these lines is asked to share with us an activity that can be considered useful education in the Anthropocene.

I will go first by going back to the chestnuts. Visiting a National Park close to Vienna, we learned that the chestnut is a great natural detergent. Two ground and dried chestnuts mixed in a liter of water are enough to wash 5-7 kilograms of laundry. How to get enough chestnut detergent for a family for an entire year?

Shifting back from machines to humans requires that we plan again in accordance with nature and listen more to the rhythm of seasons. Peak fall is the time when chestnuts pop and drop. They need to be collected and then ground and dried. All these steps in the process of producing natural detergent are not much fun if done alone, but in a group, they would turn into a purposeful bonding activity. One which gives time to chat and joke. One which opens a door to learn more about the self, the others, and the planet. An activity that – if embraced by a wider population – would also contribute to reducing the chemical industry and residential waste water’s impact on the planet.

There is no one-rule-fits-all, but I believe that we need to find more of such community building activities that not only engage children but also youth and adults. What sociologist Hartmut Rosa described in his book titled Acceleration and Alienation is like an invisible disease corrupting our societies.

We are tempted by convenience, but loose community, and in turn, we compensate for increasing isolation with uncontrolled consumption. Technology has given rise to an unprecedented scale of nihilistic individualism, where we can satisfy almost every materialistic want with this little tool of modern man called “the smartphone”. Creating a healthy behavioral architecture for our children through manual engagement in a purposeful environment will help them and the planet.

SOURCES:

Angeline Stoll Lillard, Montessori: The Science Behind the Genius

Maria Montessori: What you should know about your child, p114