Author:

Knut Wimberger

Short summary:

Covid-19 exposes the flaws in the education system and provides an opportunity for change. On the contrary, pharmaceutical companies are gifting us with vaccines that allow adults to keep their jobs and children to attend their schools despite mutations of the virus. Stubbornly, we cling to a system that has already begun to disintegrate all around us. How else can we interpret the progressive destruction of nature and society? A systems theory perspective from a father of two pupils.

Educator and journalist Karl Heinz Peterlini eloquently described in a daily newspaper on April 25 2021, just before the resumption of full classes after the spring lockdown, how Covid-19 exposes the flaws in the education system and provides an opportunity for change. Another winter has rolled in, strengthening the virus and sickening the population, yet there is no evidence suggesting that we are capable of systemic change. On the contrary, pharmaceutical companies are gifting us with vaccines that allow adults to keep their jobs and children to attend their schools despite mutations of the virus. Stubbornly, we cling to a system that has already begun to disintegrate all around us. How else can we interpret the progressive destruction of nature and society? A systems theory perspective from a father of two pupils.

Seeing the Light at the End of the Tunnel

December 9, 2021.

I walk with our thirteen-year-old daughter after dinner from our apartment to the vaccination center while our nine-year-old son stays at home. It is pitch dark and the icy snow of the last few days crunches under our shoes. I have booked her the second and myself the third shot, although I am anything but convinced that this is the only way out of this situation, as the director of the state education office wrote in a letter to parents on November 24.

The vaccination center is spacious and seems surreal. Smooth gray concrete on the floor. Bright yellow walls and ceilings. There is a quiet, almost solemn mood that reminds me of a funeral. We are directed to the tables where we fill out the medical history questionnaire and walk quite a distance without encountering another person until our next assigned stop. What vaccination did you get last time? one of the two young doctors asks. My gaze wanders to the booths, where it says BionTech/Pfizer on the left and Moderna printed on a piece of paper on the right.

Red pill or blue pill? It makes no difference. We are pragmatic and want the stamp on the vaccination card, which, like a driver's license, currently entitles us to navigate society and prevents divisive discussions. The comparison is apt. Just as a driver's license says nothing about the owner's actual driving competence, the vaccination says nothing about protection from disease or for fellow human beings. In our daughter's case, this is evidenced by the fact that she continues to be tested at school three times a week and has to wear even when sitting a face mask - despite being vaccinated twice.

After receiving this stamp on our vaccination cards, we join the few other vaccinated people in the waiting area. “Wait for 10 minutes”, Zoe whispers to me. We sit down and I start flipping through her immunization record, which is kept together with the mother-child passport. When I find the pregnancy tests, memories come flooding back and I abruptly start telling Zoe about the first 18 months of her life, especially about her birth at the Semmelweiß hospital in Vienna. About the pregnancy gymnastics that drove me crazy. Of her mother's calmness before and bravery during her birth. Of the screaming of the other women. Of the breakfast in the morning and the short drive to the clinic afterwards. Of the birth itself, just a little later, at 11:59 on May 25, 2008.

Zoe listens to me spellbound. I feel connected to her as I rarely do and wonder why it takes moments like this to really connect with your own children. The routine of everyday life is mostly just a side-by-side but not a togetherness. We are too busy to be able to come to rest. I look into her eyes and close my story: "Your birth has changed my life like nothing else. You and your brother are at the center of everything I do. We stand up and stroll out of the great hall towards the exit in jolly spirits. One last look back and I think to myself: in every experience you can find something positive if you let it happen. I am grateful for the conversation with Zoe, and this rare feeling that people of a western society can have a common denominator. I have a hunch that it will be the relationship between parents and children that will determine the outcome of this multi-layered crisis.

learning what matters. now.

Zoe has not been attending classes since November 20th and will be learning at home until the end of the term despite her two vaccination. The Austria-wide regulation that children are allowed to stay at home without a doctor's release was a welcome opportunity for us - loosely based on designer Friedrich von Borries - to further exploit the cracks in the system and design an alternative. Every day I asked Zoe what she was learning at school and if she was interested. Every day I got the same answer. Except for arts and crafts classes, every school day is characterized by yawning boredom.

Economic anthropologist Jason Hickel recently wrote on his twitter account: "What's the point of an economic system that does not produce wellbeing and destroys the planet? We can ask the same question for our education systems: What is the point of an education system that produces unhappy adults who don't know how to secure our species' survival?"

The interaction of economics and education is a chicken-and-egg problem: Which comes first? Which system is causal to the development of the other?

The government's unwillingness to sustainably transform the education system is driven by the economic system in which education is embedded. The nation that first shifts from competition to well-being could be overtaken and out-performed by the others in the prevailing rat race. And yet, it is in economic competition equally critical to be innovative and able to think beyond prevailing paradigms as it is for the design of a new way of living. We need to change both hen and egg at the same time.

After three years at a Hong Kong school and three at a Chinese school in Shanghai, our daughter received her first report card from an Austrian school this January. It was probably the memory of my own school days that made this unspectacular moment so formative. I immediately looked for my document folder and flipped through to find my report card from the same grade. The two documents lying side by side confirmed my first impression: despite exponential technological change, the school system has not changed between 1989 and 2021.

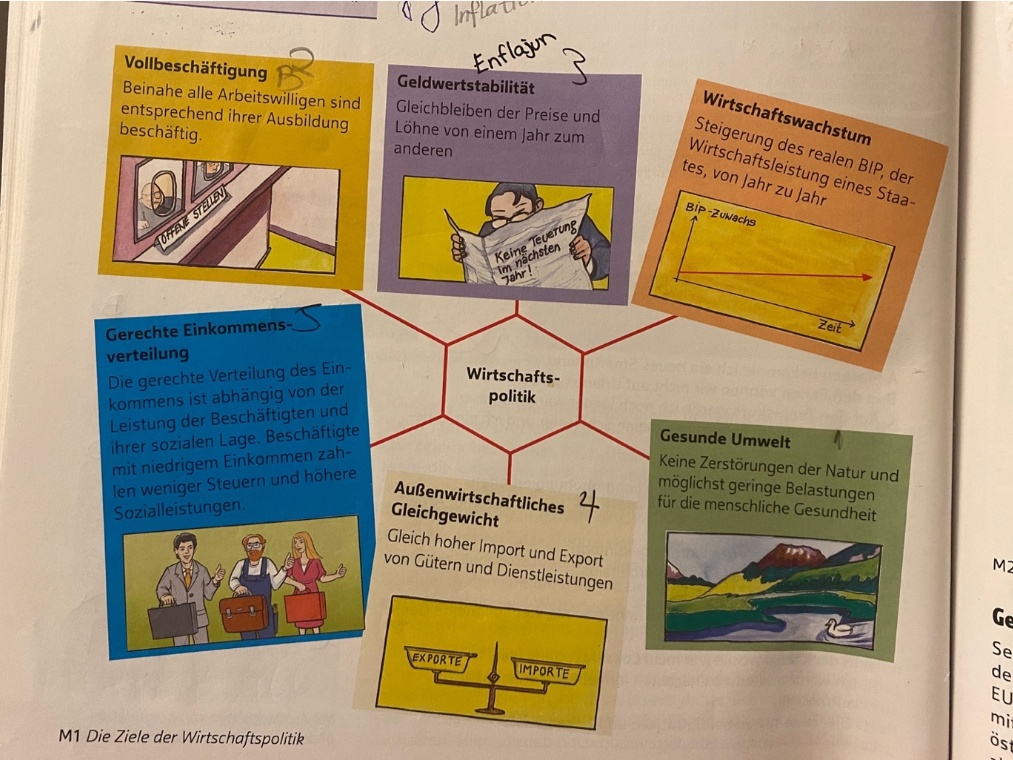

Our children are deprived of health and happiness in the same short lessons with too much and irrelevant content. 98 percent of instruction takes place indoors, is delivered by often frustrated and bureaucratically overburdened educators, and kills the child's natural learning instinct by regurgitating outdated content, such as presenting economic growth as a core economic policy goal.

A visual explanation

of economic policy goals in a 7th grade geography text book.

Zoe currently attends the eighth grade in a local secondary school and is listed as an extraordinary student until summer, so she is officially not assessed in any subject in which she has not yet reached native language level. However, the school system, which is characterized by economic competition, has already broken through this non-assessment, which is in itself stipulated in the school law, and has eroded a good part of Zoe's natural self-confidence. She grew up with Chinese as first language and English as her second. Just recently, she casually said she wasn't good at math or English. “But how many of your classmates can sing several English songs without accent and by heart?” I asked her. “That has nothing to do with English”, was her answer. And she is unfortunately right, because the school subject English allows secondary teachers to emphasize comma punctuation and to ignore musical skills. Ken Robinson is probably the best-known educator who has bemoaned this sick focus on robotic language skills and the extensive neglect of arts & drama.

Instead of seeing a student from a different culture or with talents and interests that deviate somewhat from the norm as an enrichment and slowly welcoming them into the class and school community to introduce the German language through play, stories and empathy, Zoe was rewarded with one “failed” after the other in tests and schoolwork. Talks with the head of the class and school adminstration helped only to a limited extent. “There is little room within the current curriculum”, the principal explained to me in her office, pointing to the school code in front of her. A cold shiver ran down my spine. How could anyone give up so much of their calling as a teacher? Was there ever one? Are we talking about a product, an inmate to be measured by the law, or a human being to whom, with all our belief in the goodness of our very nature, we give enough space to develop to the best of our ability?

Since November 20th Zoe is at home and I help her to find a new rhythm. Participate only in the most necessary hours online. Sufficient sleep, as neuroscientists have been demanding for adolescents for years and as should be the rule for all children during the dark winter months anyway. Use the time freed up for your own interests. More energy and thus also a renewed desire to sing and make music, Zoe's central talent, which has absurdly died off in the music branch of her secondary school. “We don't make music, we only do music theory!” she complained. Daily yoga to strengthen body and mind in a self-determined way. The transformation is not easy. It requires commitment from child and parent, and I can only accompany Zoe in this process because I am not tied to office hours.

As an environmental educator, I take my children on short and long nature explorations and observe their interest in a wide variety of encounters. During one of these afternoons outdoors, Zoe asked me why there is oxygen in the atmosphere and why we have it on earth in the first place. A nice conversation developed, and I was pleased to see that the embers of curiosity had not yet completely extinguished. Questions of this kind are like sparks that can ignite a fire.

I remembered the Big History Project, which I had studied a few years ago as a best practice for self-directed learning. Zoe was ready for it. Since late November, after a brief introduction, she has been learning independently and we discuss her progress each day. She keeps a journal about the course in which she notes or draws anything that seems relevant. Zoe has already reached chapter three, which explains the history of evolution, and this week she has found a detailed answer to how oxygen evolved on earth and how the atmosphere formed.

I'm delighted that this transformation of learning is happening like this with Zoe, but the start of regular classes hangs over us like a sword of Damocles - a letter from the principal earlier this week admonishes parents that while they may leave their children at home without excuse, they must be graded at the end of the semester. Even under these extraordinary circumstances, competition rules. I wonder what it would be like if many parents were on the same page with us. Steering peacefully and prudently in a new direction because we are convinced that a post-industrial education system that takes into account the individual needs and talents of our children will result in well-being and happiness for both our families and society.

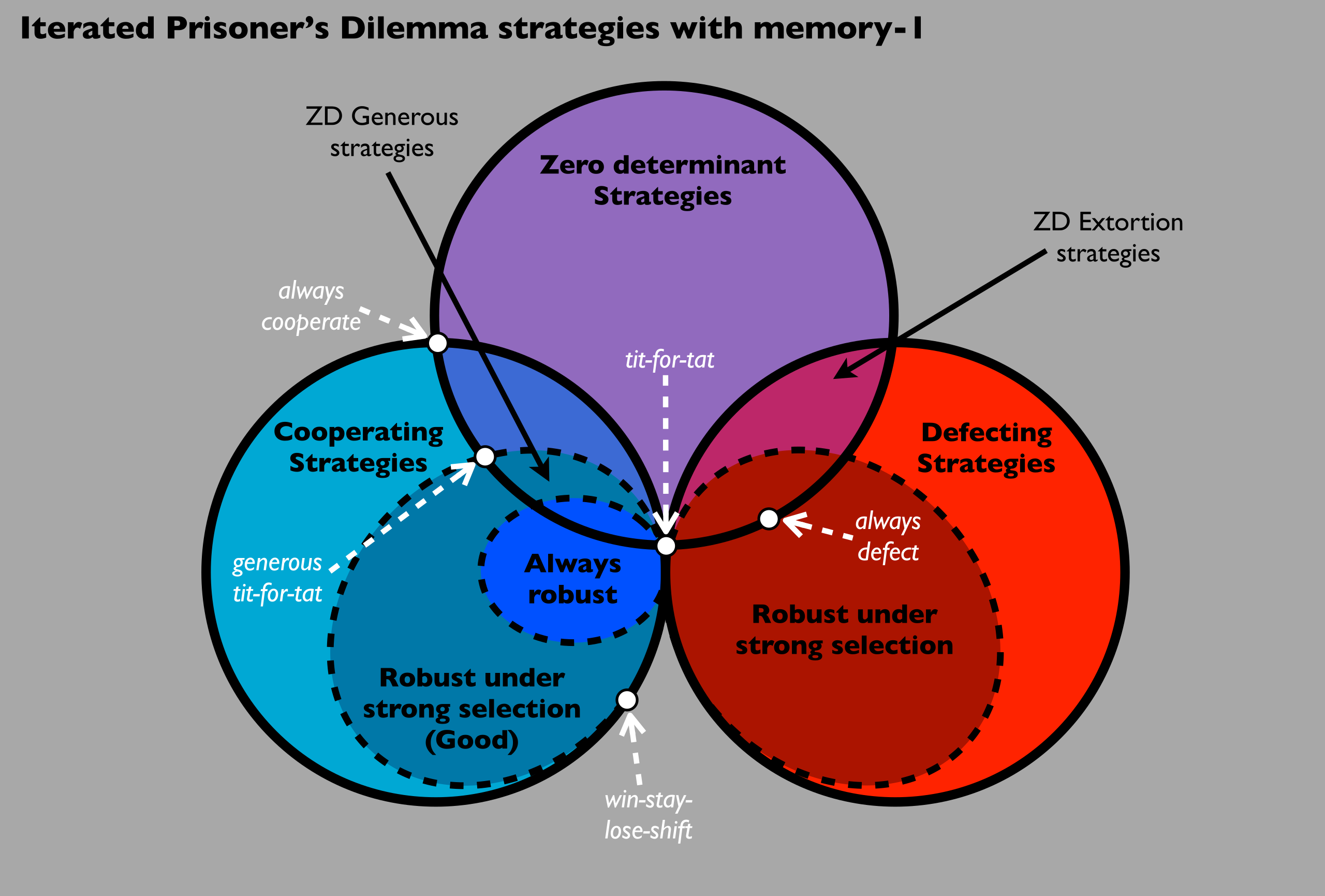

the prisoner's dilemma

Francis Fukuyama's comments on the Prisoner's Dilemma brought me to an important systems theory analogy that has profound relevance in the context of transforming education systems. The Prisoner's Dilemma is used by economists and evolutionary biologists to explain cooperation through reciprocal altruism. The central question to be answered is: how do rationally but selfishly acting players arrive at cooperative norms of interaction that increase not only their own but also group welfare?

This classic problem in game theory is described thus: Sam and I are in prison, and we agree to break out together. If we cooperate, we can escape, but if Sam reveals me to the guards, then I will be severely punished. On the other hand, if I give Sam up to the guards, then he will be punished and I will be rewarded. If we both expose ourselves, then no one will receive any benefit. Therefore, we will both get off better if we cooperate and stick to our agreement, but the risk of Sam revealing me is substantial, and I get a reward if I reveal him to the guards. Therefore, we both decide, separately, that we will betray each other. Despite the mutual benefits of cooperation, the danger of going out as a betrayer thwarts the manifestation of the benefits.

Systemically, members of a society are inmates of a prison. The capitalist paradigm binds us into competition and obligates us to send our children to educational institutions designed for competition. Instead of learning and teaching compassion and empathy, our children are literally being trained in survival of the fittest, even in the context of a severe flu epidemic that paralyzes society for several months and hits many families hard, especially those from lower-income backgrounds.

That Herbert Spencer's Social Darwinism was a dead end has actually been clearly demonstrated. That symbioses between organisms create a survival advantage in times of crisis has been proven many times in evolutionary biology. Nevertheless, our society is drifting apart. We are superficially divided into vaccine deniers and vaccinated as in times of the Spanish Inquisition. As the cultural critic Neil Postman wrote in the 1990s, the deepest Middle Ages prevail, but the technology that surrounds us everywhere makes us believe that we have evolved. No. We haven't. We still suffer from a limited consciousness that does not want to see that we should strive towards each other.

How does this divergence manifest itself in education, the most important lever of a society that wants to achieve social permeability and equitable redistribution of wealth? The public school system is increasingly being undermined by private schools in a way I know only from China. In Shanghai, for example, which we called home in 2009 until 2020, there are over 100 international schools where parents who can afford it save their children from the highly selective state system. In Austria, private schools are popping up like mushrooms of the same breeding ground: an increasingly competitive knowledge and information society.

While private schools were a rare exception when I was a student, they are now an integral part of the educational landscape even in the welfare state of Austria: recently, the International School Krems was opened in the Göttweig Abbey, there is an International School in St. Pölten, the integrative Montessori Atelier has been trying to carve out a niche for itself for several years, the renowned Lernwerkstatt in Pottenbrunn near St. Pölten has been attracting a group of parents interested in reform education for 20 years, in Linz the Anton Bruckner International School has joined the Linz International School, and so small towns offer what until now could only be found in Vienna: alternatives to the state system.

The inconspicuous example of the Integrative Montessori Atelier in St. Pölten gave me first-hand experience of the social spectrum of families interested in private schools: an upper middle class of exclusively Austrian nationality who can afford to bring their children to school every day from country estates up to 50 km away. In contrast, the public elementary school next door enrolls up to two-thirds children with immigrant backgrounds and Islamic creeds. The salvation being sought is therefore not just one of access to the labor market, but also to a form of culture. The knights of the West are still fighting with the pagans of Asia Minor.

That this alternative is experiencing both supply and demand is remarkable in itself, as changes in the educational landscape point to profound changes in society. Management philosopher Peter F. Drucker, who has described and predicted with unparalleled clarity the changes in the labor market and the demands on the worker since World War II, let us know more than 20 years ago that information societies will be more competitive than any previously existing human form of organization. That this competition would increasingly affect the education system was to be expected.

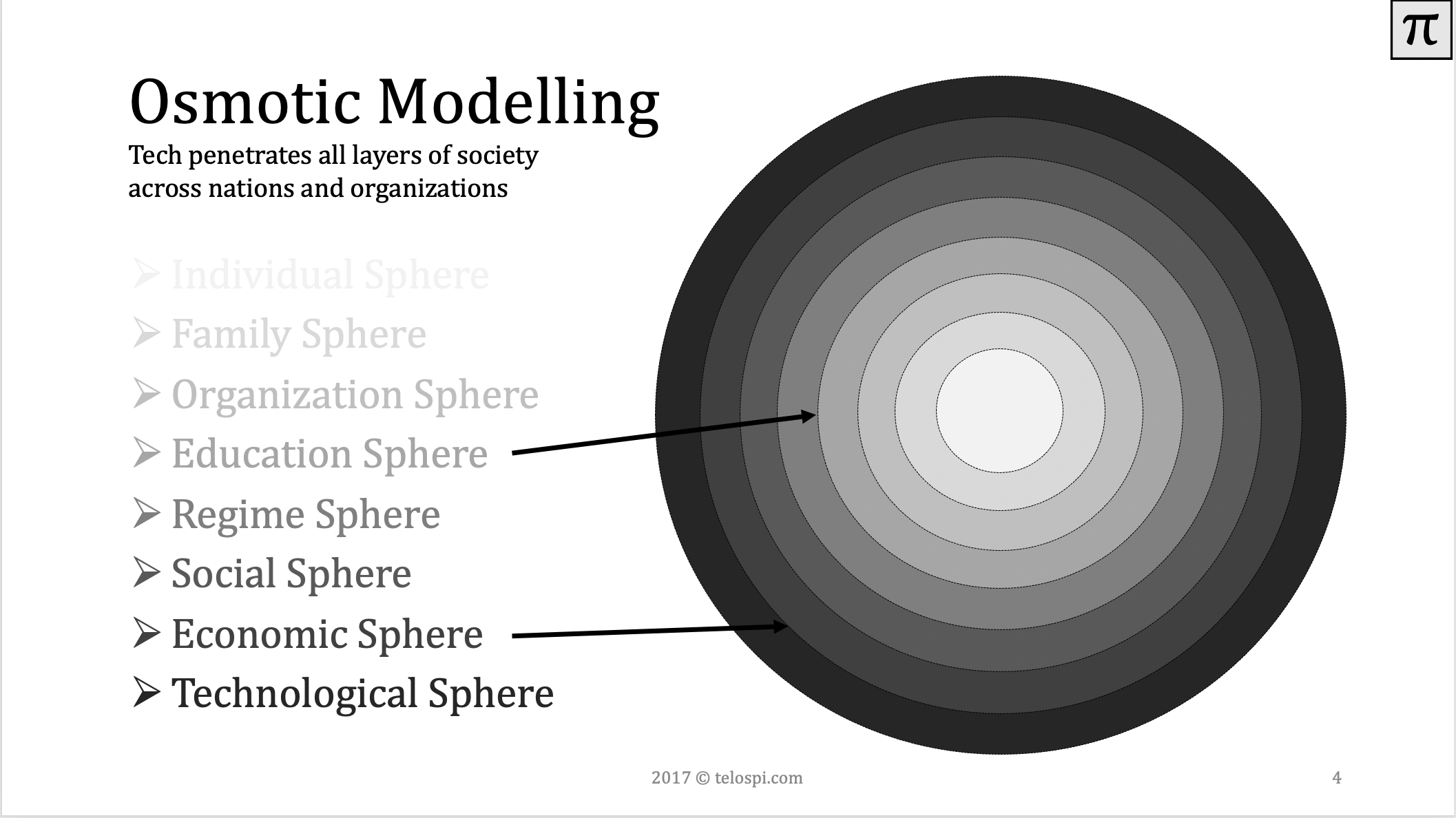

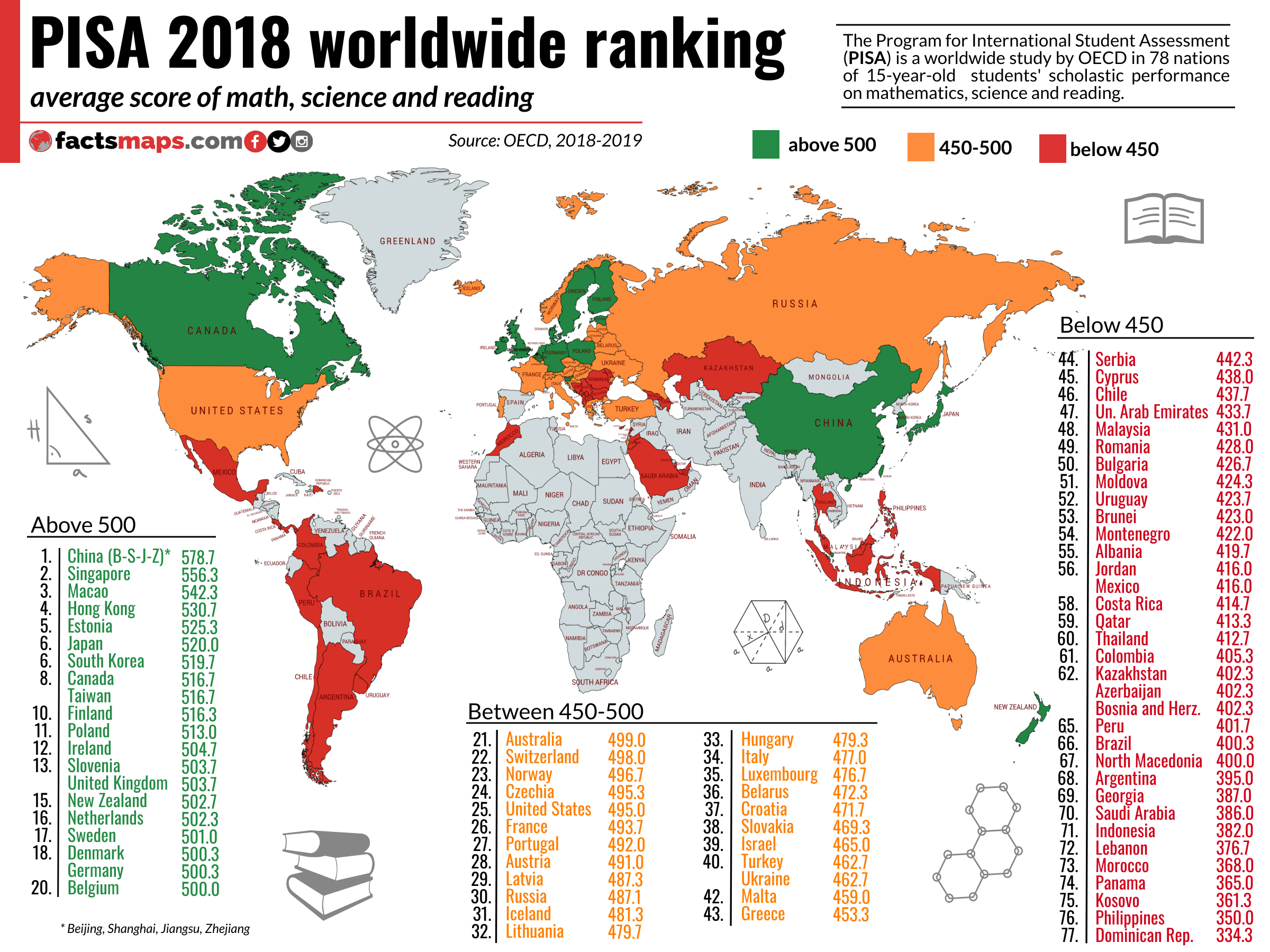

Global Gulag vs Global Community

What is overlooked by parents as well as national education policy is that while labor markets were largely regional in the 1980s and 1990s, they are transnational or even global in the 2020s. From the perspective of the evolutionary biologist, the dimension of the ecosystem has shifted: Whereas it used to be sufficient for a person to survive in (educational) competition in a spatially limited ecosystem, the technological acceleration of the last 50 years has created a global labor market that attracts and retains educational elites in a few centers such as Beijing and San Francisco, while the periphery is increasingly left behind. A perhaps nesting but factual note: Austria is already part of this periphery.

Technological change has created a global gulag in which only a privileged few can save themselves from the evolutionary-biological surf onto safe shores. The progressive population growth to almost eight billion people has furthermore created a situation which generates a so-called behavioral sink, especially in the education and health care systems, due to Covid-19. The behavioral sink was first described in the famous mouse utopia experiments of the ethologist John Calhoun and shows that in mammals with too little retreat space, epidemic behavioral disorders and mental illnesses occur with significant higher frequency than in populations with more space and peace.

A global market based on economic competition, in which nation states are the largest competitors, reduces their citizens to armies in a battle that is no longer fought on bloody ground but in the fields of research, innovation and education. Unconsciously, we support this system by sending our children, like mercenaries, to schools where what counts is not cooperation and empathy, but competition and a sense of achievement.

Those parents who send their children to private schools think they are saving them from competition or giving them a better starting advantage in that competition. But, to return to the Prisoner's Dilemma, they are actually giving away other parents who cannot afford this luxury or who have already courageously chosen post-industrial learning and no longer want to expose their children to the eternal rat race.

I want to elaborate on this analogy again because the dimensional leap is a significant one: whereas in classical game theory the ecosystem is a prison, i.e., a territorially restricted space, and two prisoners agree to break out, we must note that in terms of work and education in the 21st century we operate in a global ecosystem that is not territorially restricted. Those who see themselves as prisoners in this education and labor market must come to an agreement to break out together. In education, too, there is no planet B.

Assuming that such an agreement has been reached, all parents, who continue to send their children to schools which are geared to competition, expose other parents (and thus their children) by implication to the system guards. Education authorities, directors and teachers, must be therefore recognized figuratively as traitors and agreement breakers.

The question that now arises, as in game theory, is the following: How can betrayal be made so unattractive that the parties stick to their agreement? How can the social surplus value of having all the children of our society participate in a post-industrial education system be made so interesting that parties are bound to their agreement (the social contract already described by Jacques Rousseau)? Francis Fukuyama explains the framework and why recognizing a "socially suboptimal outcome" is central to the solution:

Prisoner's dilemmas are problematic for their players because the solution in which both players cheat is called a Nash equilibrium by game theorists. Cheating is the best strategy available: it minimizes the likelihood that you'll get into what's called a "sucker payoff," where the other player gets away with a reward for blowing the whistle because you stuck to your agreement. At the same time, you have the opportunity to do the same to him. But while cheating is a better strategy for you as an individual than cooperating, it leads to a worse outcome when the actions of both players are taken into account-what economists call a "socially suboptimal outcome." The question, then, is how the individual players can arrive at a cooperative outcome.

What game theory somehow overlooks (at least in Fukuyama's explanations) is the not insignificant role of prison guards. These guards are not only external agents in the interaction between the two prisoners who have reached an agreement, but also potential inmates. For if the conditions in the ecosystem concerned become so unbearable that even the guards begin to doubt that they are earning their bread doing the right work, they become potential accomplices of the prisoners in breaking out or changing the system.

Applied on our societies, we have to ask ourselves who these guards are and who benefits from the ruling power structure. That this power structure does not achieve economic justice, community empowerment, true education, and successful preservation of our environment should no longer need to be argued. Wealth concentration as it was before World War I (Thomas Piketty), corrosion of community and family (Francis Fukuyama), propaganda and production of unhappy children (Ken Robinson), and ecological collapse (Fritz Schumacher) have been logically and stringently laid out by renowned authors.

Viewed soberly, it is the bureaucratic apparatuses of Western democracies that, as watchdogs of the wealthy, keep a sick system alive. It is these thousands of civil servants and contract employees in municipalities, cities, states and the federal government who, in the sense of game theory, have only the slightest interest in changing the status quo. They earn above-average wages, generally work below-average hours (I was at home in both worlds for several years, and know what I'm talking about), and change professionally only when they strive for meaning and self-fulfillment.

Vast parts of national budgets are spent on education and health in our hydrocephalous state entities, it is therefore necessary to explicitly highlight all employees of public educational institutions and health care facilities as extended arms of the bureaucracy and thus guards of the prison. It is the teachers who may have started their careers enthusiastically, but after years rendered numb by the system, do their work only as a bread job. They are the doctors who work their way up the hospital hierarchy to the position of senior physician or primary physician and, on the side, become or remain rich in their private practices with the illness of a sick society.

Exactly this circumstance explains why in the recent demonstrations in Vienna, where thousands took to the streets, aggression was shown against hospitals and in the fall 7500 children were taken from public schools: the citizen feels more than ever as a subject of a dominant power structure, which is more interested in self-preservation than in the common good. The problem, in other words, is only secondarily the agreement between prisoners. It is primarily the lack of moral responsibility on the part of the apathetic guards who don’t stop to support a system that is obviously causing harm.

Here is a second criticism of game theory, which is even more fundamental than the first: Why does game theory assume that the system observed is a prison and that the two who come to an agreement are prisoners? Who sentenced the prisoners to their term in jail and for what reason? A study of the primary literature on the prisoner's dilemma and Robert Axelrod's reflections on the question of how cooperation among humans arose is definitely required at this point but goes beyond the scope of this essay.

We can however summarize that the Prisoner's Dilemma assumes a prison situation and thus automatically forces every citizen in society whose will to cooperate is being examined into a prisoner position. Thus, it is not a free individual in an enlightened and fair society, but a subjugated and cornered being, which cannot bring about a change in the system by strategy, but only tries to get the best possible advantage for itself within the given system conditions by tactics.

Aldous Huxley already indirectly exposed this assumption error in 1962 with his essay The Politics of Ecology, in which he revealed the human striving for power as the essential cause for the destruction of nature. He describes that the central problem of human nature is not the cooperation between two prisoners, but the temptation of power, which permanently tempts any person in power to abuse it. The situation to be thought through in game theory, therefore, is a guardian's dilemma: under what conditions does the guardian decide to cooperate with the prisoner and, instead of an escape (and therefore the continued existence of the prison), initiate a breakup of the prison?

It is exactly this situation that must interest us in a society, because what we need is a transformation from power-abusing structures, both within democratic and dictatorial systems, to a global structure of responsible freedom. In more economic terms, this means reducing government intervention to a minimum, because it is within the public sector where the greatest potential for system optimization resides, and where decisions are made on a wide scale that are neither economically nor ecologically sustainable. The mere fact that thousands of contract employees are funded by the imprisoned citizens through tax levies to in turn raise their children to be prisoners should be enough to make one realize that we need a fundamental system transformation that must start with a lean state.

The sixth mass extinction

Realistically, neither enough bureaucrats nor enough parents will realize that maintaining the current competitive educational institutions, whether public or private, will lead to a socially suboptimal outcome. Blood is thicker than water, and we think that investment in the industrial education apparatus will at least enhance national competitiveness. Likewise, we think that ringing names like Mary Ward or Sir Karl Popper Grammar School will protect our children from the lurid surf of automation and displacement by striving Asian students in the global labor market.

Anyone who has even a rudimentary understanding of China's dimensions knows that economic entities like Austria, which at best can be compared to a second-tier city like Hangzhou, and even the European Union as an economic bloc, are being washed over, undermined and booted out by China in a global economic structure shaped by capitalist principles. There is no escape from the economic and social consequences of a strengthening of Asia as a whole, or of entering into competition with a totalitarian organized superstate like China. Suddenly having 500 million to a billion people above us in the global pecking order can either be fought with more competition, especially among our children, or ideally accepted in a relaxed manner with an alternative strategy.

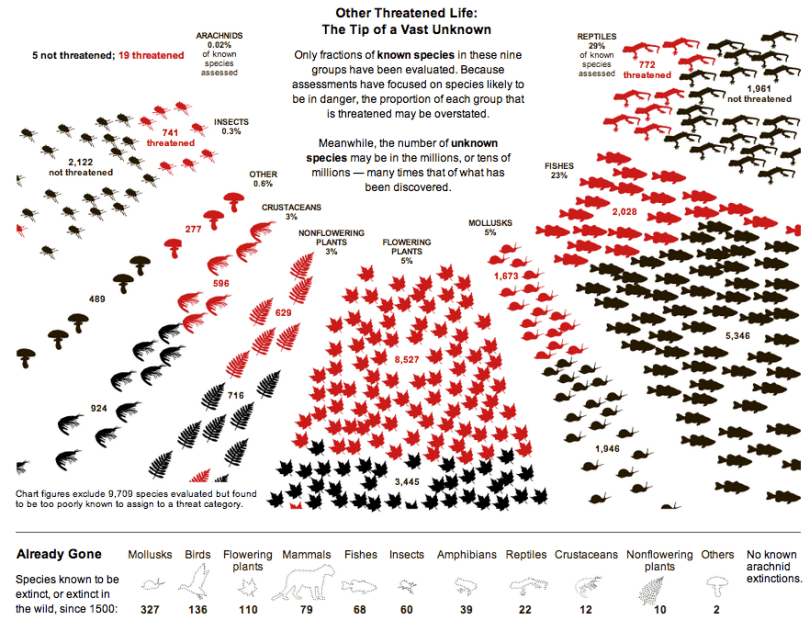

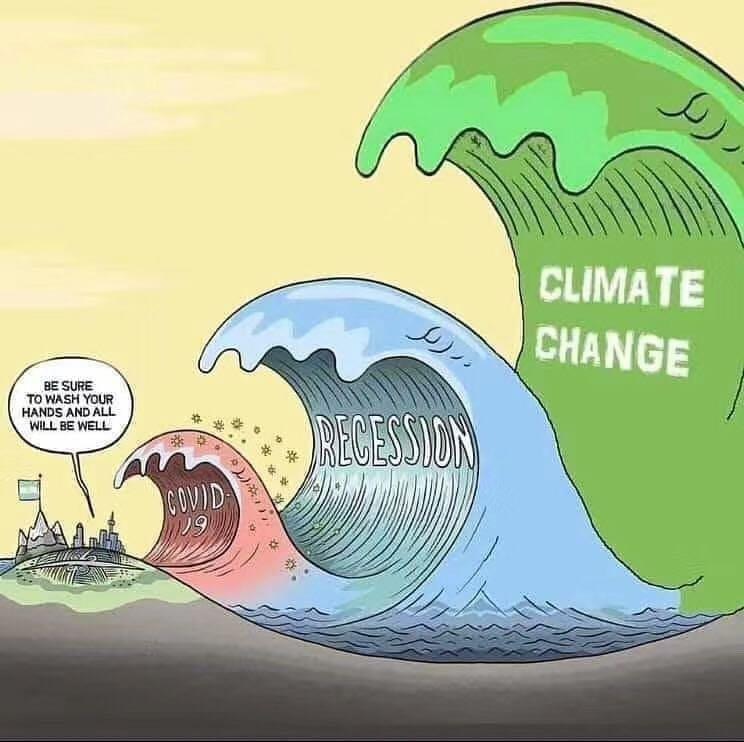

Whether we will succeed in this rethinking depends very much on how quickly our environment changes, i.e. how quickly the climate crisis leaves us with no other way out than to switch to cooperation and keep the agreement to break out of prison. For lack of perception of the large systemic changes, the change of the immediate living space must teach the necessary lesson. As the saying goes, he who will not hear, must feel. A renewed look into evolutionary biology illuminates what we can no longer recognize as observers but as participants: The five identified mass destructions in the history of the earth are described as consequences of excessive competition in an ecological niche. In the Anthropocene, humans have allowed the planet to become a single global ecosystem, which can also be seen as an ecological niche: it is the only place in the known universe where we are able to survive.

The sixth mass extinction, which is undoubtedly underway, will in evolutionary terms end the competition within our own species to stop excessing the carrying capacity of the planet. So, unless we can learn to act cooperatively and devise, write, and keep a new social contract, the ecosystems around us will collapse first, suffering and death will enter the land until the biological niche previously occupied by homo sapiens has been taken over by another life form.

Whether this new life form will be a better version of man, homo illumens as I like to call him, or a virus remains to be seen. But we definitely have the possibility to influence this outcome. In any case, evolutionary biologists refer to the process of adaptation to new living conditions as "adaptive radiation": those anatomical or, in the case of humans, cultural traits that are unsustainable are extinguished, while those that ensure survival spread rapidly.

In times of planetary crisis, Earth's history has repeatedly shown that the symbiosis of two species establishes an essential advantage in the struggle for survival - a biological view of the prisoner's dilemma. Those who can overcome the fear of being exploited by others and resist the lure of short-term gains will increase their chances of survival, especially in the coming times of crisis. For this reason, community-based co-living projects that can think about housing, economics, and sometimes education in a decentralized way and live transgenerationally are lights at the end of the tunnel.

A Solution to the Education Crisis is a Solution to the Climate Crisis

In Austria, over 100 co-living projects have been established in the past 10+ years. These initiatives have often more or less succeeded in escaping one aspect of the capitalist system: for example, the rising real estate prices or the compulsion for the nuclear family or the single household to have to purchase every necessity from the screwdriver to the washing machine itself. However, the projects I have encountered fail on one central issue: education.

Here, at least two problems need to be discussed: On the one hand, there are certain educational contents within a society, regardless of whether they are regionally limited or extend globally, which are better provided centrally than having them prepared inefficiently by decentralized institutions, probably in inferior quality, from an overall economic point of view. The central question is how to make ivy-league educational content available to all children and young people, regardless of their location and economic possibilities. On the other hand, there is educational content such as empathy for oneself, one's fellow man and the planet, which is not to be worked on globally but locally, ideally as a vehicle to create and strengthen deep personal relationships.

Software entrepreneur Martin Ford sums up the central role of education: the greatest risk is that we could face a "perfect storm" - a situation in which technological unemployment and environmental impacts develop roughly in parallel, reinforcing and perhaps even exacerbating each other. But if we can fully embrace advancing technology as a solution while recognizing and addressing its impact on employment and income distribution, the outcome should be far more optimistic. Finding a way through these intertwined forces and shaping a future that provides broad-based security and prosperity may prove to be the greatest challenge of our time.

Understanding education as a public good that must not be influenced by competitive profit or power maximization is the key to finding this path. A conditional universal basic income the basis to enable this access to education. For as psychologist Abraham Maslow wrote back in 1964, the long-term goal of education - as well as psychotherapy, family life, work, society, life itself - is to help people grow to their fullest humanity, to the greatest fulfillment and realization of their highest potentials, to their greatest possible stature. A discussion of what social values we pursue through education is therefore more necessary now than ever before, but no longer sufficient. Parents - whether prisoners or guards - who are willing to offer an alternative to the state-industrial education machine must act.

further reading:

Karl Heinz Peterlini, Das gewonnene verlorene Schuljahr

Johann Heuras, Brief der Bildungsdirektion an Eltern niederösterreichischer Kinder

Friedrich von Borries, Weltentwerfen: Eine politische Designtheorie

Jason Hickel, Urgent Need For Post-Growth Climate Mitigation Scenarios

David Christian, Big History Project

Gertrude Aumayr, Brief an Eltern des BORG St. Pölten, 10. Dezember 2021

Knut K. Wimberger, Unlocking Human Potential Through Play

Ken Robinson, The Element: How finding Your Passion Changes Everything

Big History Project: Crash Course on the Epic Story of Evolution

Peter F. Drucker: The Essential Drucker

Francis Fukuyama, The Great Disruption: Human Nature and the Reconstitution of Social Order

John Calhoun, The Mouse Utopia Experiments

Thomas Piketty, Capital in the 21st Century

Fritz Schumacher, Small Is Beautiful – Economics as if People Mattered

Robert Axelrod, The Evolution of Cooperation

Aldous Huxley, The Politics of Ecology

Martin Ford, Rise of the Robots

Abraham Maslow: Religions, Values and Peak Experiences