Author:

Green Steps

Short summary:

Sept. 27, 2023 A field trip to five model school gardens in Lower Austria shows why gross motor parks should not be confused with nature experience; why primary experiences must once again become the norm; why there is no way around full day curricula; why we can no longer afford ideological arguments; and why better school gardens are only the first step on the path to school-centered nature connection.

Excursion with Familienland GmbH to model school gardens in Lower Austria. A well-filled bus leaves the provincial government quarter in St. Pölten early in the morning, after the provincial councilor Teschl-Hofmeister did not miss the opportunity to bid farewell to the delegation of municipal representatives, school principals and teachers in a manner befitting the steep hierarchies of the formal school system: "I wish you a nice day, unfortunately I can't come with you, budget talks are waiting for me, I'd also rather look at playgrounds. Behave yourselves and thank you for coming."

We cross the Danube and dive into the Waldviertel, where we visit three communities in the morning whose school gardens have been newly created or renovated with the support of Familienland GmbH. The intention is good: get out of the classes and provide more opportunities for children to exercise. However, Familienland GmbH creates a somewhat state-capitalist framework: the ÖVP-dominated state government of Lower Austria, with its offerings packaged in non-profit limited liability companies, permeates the entire cultural and educational sector in a monopolistic manner that is in itself an antithesis of creativity and free development.

The division of the country into political camps is clear at this event: I am the only representative from the social-democratic dominated state capital. All the other participants are from rural communities: still the stronghold of the Christian Social Party and thus the first target group of a state organization. One is repeated to this place constantly: who has the money, has the say. The school garden projects of the family country GmbH are promoted by the country to 50% with a project volume of maximally EUR 40k. Allegedly over 300 of such projects were already converted and one is proud to have designed different participation processes, in order to involve above all the children into the planning of the new school gardens.

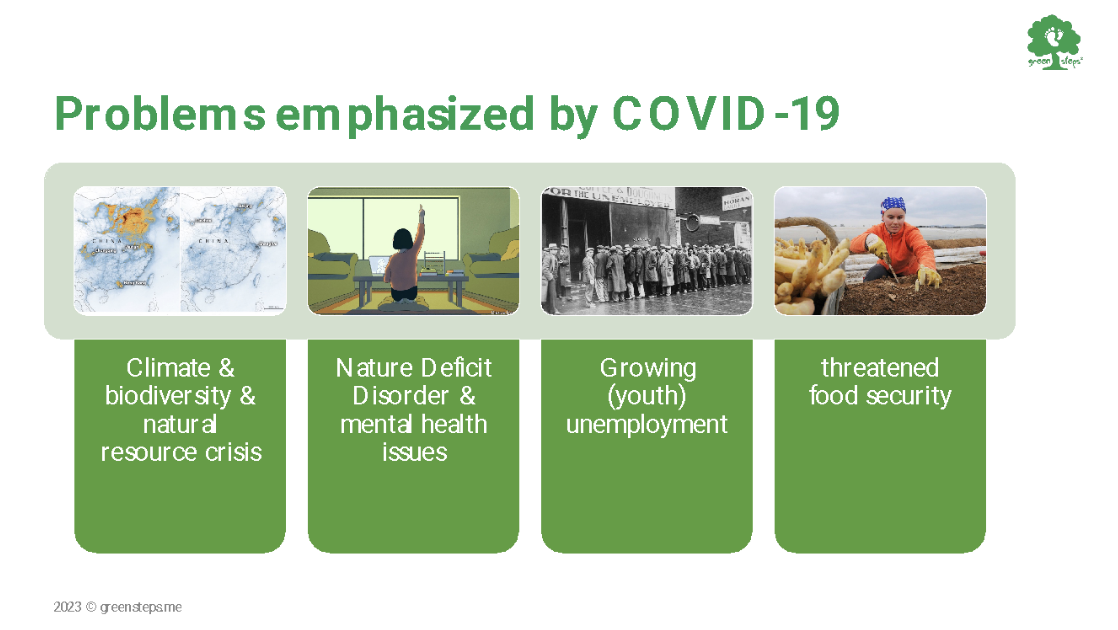

It is ideological conflicts that prevent the uniform introduction of day schools. While all-day education programs enjoy high popularity in social democratic Vienna, they are a rare exception in Lower Austria. Even in social-democratic St. Pölten, the school system is strictly separated from afternoon care. In the Christian-socially dominated rural communities, people do not want to further erode the stereotype of the rural extended family by taking children away from grandparents or from the mother who is available in the afternoon. But even Christian conservatives among the teachers see this family type dying out. The only thing standing in the way of all-day schools offering comprehensive natural-space instruction is actually the school system's inability to transform. Perhaps we still need a pandemic to recognize this inevitable necessity for our children (as well as teachers).

Our first stop is Lengenfeld, where the mayor welcomes us at the door of the educational campus. An architecturally excellent project that successfully combines old building fabric with new. The small school garden was renovated and opened during the Covid pandemic. Two elementary school classes sing us a song and the director describes her experience.

As already known, the role of the school warden is emphasized. Anyone who studies place-based education must sooner or later come to the conclusion that the director of a school must also be the head school warden, assisted by a team of landscapers, gardeners and repairmen, who consist in an ideal scenario of students, teachers and parents. The small elementary school has only 68 students, who can enjoy a garden that includes some old chestnut trees. The renovation has brought a slackline, a climbing wall and a crawling net. Based on her experience, the principal has eliminated the swing and slide from the concept, because "in front of and behind the swing there must be constant supervision, and with the slide the girls want to get down, while the boys always just climb from the bottom to the top."

Our second stop takes us to St. Leonhard, where the middle school recently closed. However, the remaining cross-year elementary school classes populate the inviting playground next to the school with noisy liveliness. Children are tinkering with the water pump and building a dam in the adjacent sandbox. In addition to the climbing wall, balance beams and climbing nets, there is also a slide and a pavilion. Since this school garden is not spatially separated from the village, it was designed to be intergenerational. The pavilion, which is covered with straw, invites children to linger after school with additional seating and exchange bookcases.

In St. Leonhard, it is noticeable that the school is truly a part of the village. Perhaps that's why parent participation in planting was so high. Vandalism, according to the municipal secretary, has never been a problem. On the contrary, people help together to maintain the garden. The rural youth and the building yard have contributed a lot of their own work making the place suitable for children. The children have a 30-minute big break, which they spend in the garden every time they go for a walk.

Primary vs. secondary experiences

After visiting two elementary school, I expect to gain new insights at the third stop in Groß Siegharts. There, the municipality is investing the impressive sum of EUR 6 million to build a school center that will house a middle school, a special school and an elementary school. The reconstruction and extension of the building, which dates back to the 1970s, is almost completed, and the new school garden is already in use for a year.

While the municipality representative holds an overlong speech and does not let the principal come to word, I ask the sidelined principal about the behavior of the middle school pupils. He tells me that they mostly hang around the swing and the wooden shack, but are difficult to be motivated to anything else. He thinks that’s normal for adolescents reflecting a general misunderstanding about human nature in teachers.

The municipality representative is surprised that even in Groß Siegharts the most attractive elements are the water and the sand. I remember Richard Loev's book "Last Child in the Woods", in which he describes that our children have less and less primary experiences. Everything is taught, on chalkboards and whiteboards, via print and digital books, movies, animations, and of course the Internet. Secondary experiences are the rule in the education system of the modern age. Primary experiences have become the exception.

A school garden has the potential to bring primary experiences back to the forefront, but engineers, landscape designers, and school staff mostly lack the insight for which any nature educator requires only common sense: predetermined, repetitive infrastructure elements that primarily promote gross motor skills are not enough to provide children with free play and stimulating moments within the school system. The industrial education of the classroom often continues in the schoolyard and garden.

Children need primary experiences that are not planned. The water pump and sandbox make this possible because water and sand are ever-changing elements that children can shape and yield to. It should be the goal of school gardens to proliferate such interactions, rather than using the same elements over and over again as an industrial standard.

Built vs. Grown Infrastructure

True open space design begins with the plants we grow, raise, and nurture through the seasons in the school garden, or the biotope that hosts a variety of insects at the start and end of a school year. The process of gardening creates a second form of infrastructure that is constantly changing. While initial costs are low compared to gross motor parks, an organic garden must be maintained on a daily basis and the fruits of that labor are often literally years later to reap.

In talking with five principals whose lunch table I join, the problem of who to take care of gardens during summer immediately comes up. No one would be found over the summer months and the school warden would have to take on more and more agendas without extra pay. The school warden, who has to spend more and more time maintaining outdoor infrastructure, seems to be an increasingly in-demand person, and I joke that I'd be happy to train for part-time positions.

The boring effect of a school garden planned without a well-thought-out grown infrastructure is shown by the Groß Siegharts project, which is highly praised by the representative of the municipality, but is deeply disappointing. A single tree provides too little shade, which he wants to remedy with sun canopies. The few shrubs are trimmed back like in a graveyard. How nearly 200 students are supposed to thrive and feel comfortable in nature at this site is a mystery to me. The principal points to a tournament-ready soccer field where, as at any school, only a certain group of students will be found.

Open vs. Closed School Gardens

One problem with the Groß Siegharts site may be the separation of the school garden from the rest of the twon, which would allow for ongoing community participation. Our fourth stop, in Groß Gerungs, shows how an open school garden adds value for local residents and spurs participation from other community groups.

Also planned during the Covid pandemic via videoconferencing and emails, the sponsorship of Familienland GmbH launched a small movement. The Gross Motor Park was completed by the students of the polytechnic school with a homemade open space classroom. The rural youth contributed three raised veggie beds, some outdoor loungers and a grape hedge. One can sense that something is on the move in Groß Gerungs.

The head of the middle school and the head of the elementary school explain that Covid has had an extremely positive effect in Groß Gerungs, because the children have gradually been forced to go outdoors during their breaks. The redesign of the school garden therefore received a positive tailwind from Covid and it was clear to all involved that children need to spend more time outdoors. Again, the necessary support of the school caretaker is highlighted, as well as the ongoing coordination between the school and the building yard for the maintenance of the infrastructure.

Is 20 minutes of outdoor time enough?

Nevertheless, I am appalled at how little awareness there is of the most elementary problem of our education systems: space. Both school principals are justifiably proud of the rapid and unexpectedly extensive implementation of the EUR 70k project, but express satisfaction that the children now spend 20 minutes a day - in almost any weather - outdoors.

When a human being, whose developmental-psychological nature is to run around, is forced to sit indoors all day, it is logical that the children are already happy about 20 minutes of outdoor exercise. But the question we need to ask here is a different one: is 20 minutes of outdoor time enough to raise healthy, creative, environmentally conscious children?

While the upgrading of school gardens and yards, which Familienland GmbH has thankfully taken on, is an inevitable measure, especially at the elementary school level, to free our children from the industrial educational prison and better prepare them for the climate crisis, a reformation of the curriculum and an integration of the space that surrounds the school and forms the children's survival space is urgently needed.

As Maria Montessori writes, "the child is in need of an environment in order to develop himself. Having accepted that, the next point is, what are we to do? What sort of environment must be prepared for the child so that it may be of assistance to him?" Already in the 3rd and 4th grades of elementary school, children are ready to leave the school garden and explore their surroundings. It is in the years of late primary and early secondary education that we form in our minds the landscapes that will accompany us throughout our lives; to which our impressions as adults will be oriented and remembered.

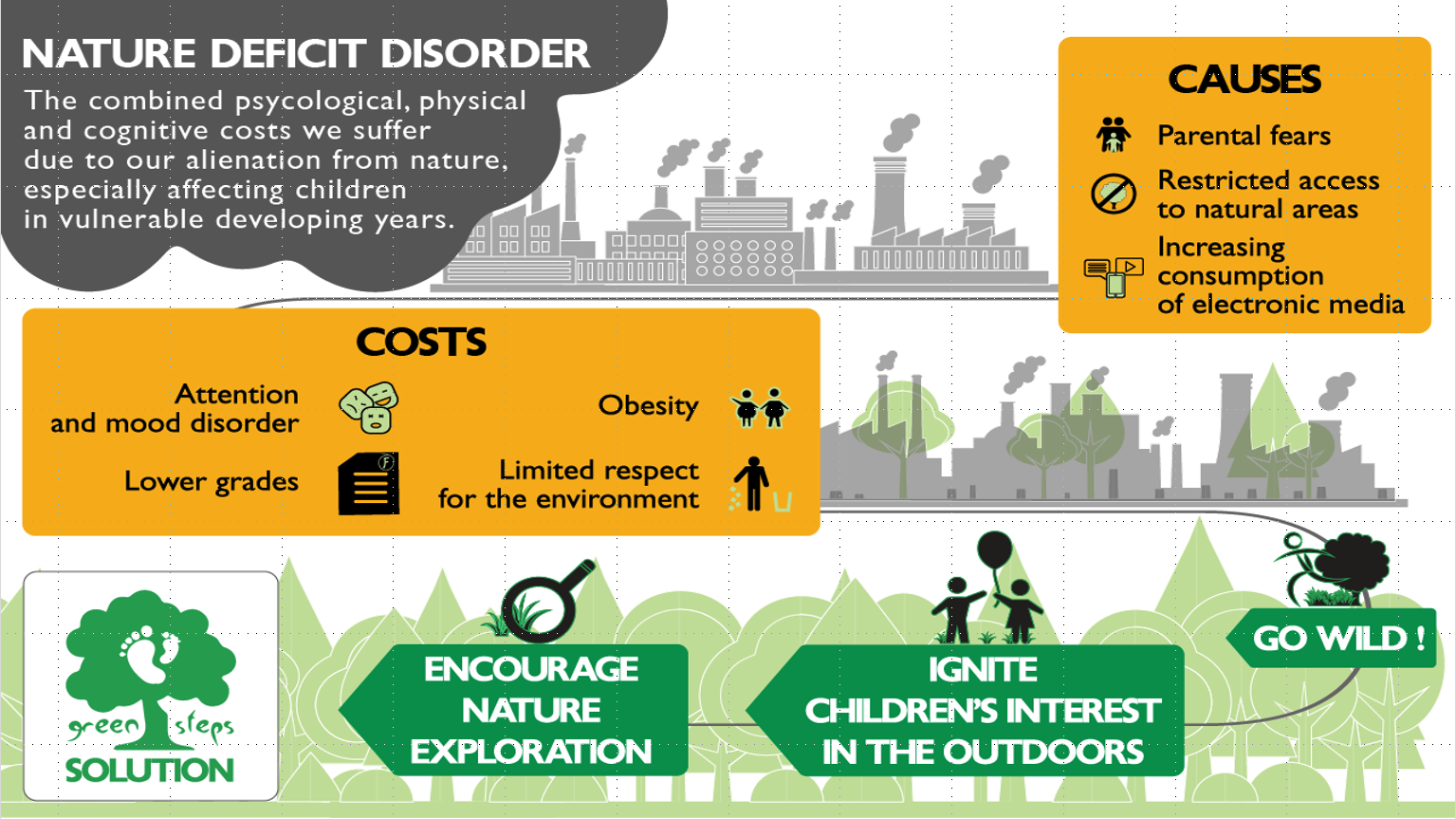

At the very least, we have already produced a generation of people who have little experience of natural areas and have spent most of their childhood either at home or at school. Especially among lower secondary students, who would actually be capable of exploring and positively shaping commons and regions, the adherence to curricula combined with digital consumption is having a devastating effect.

Mobile Campus 4.0 as a solution

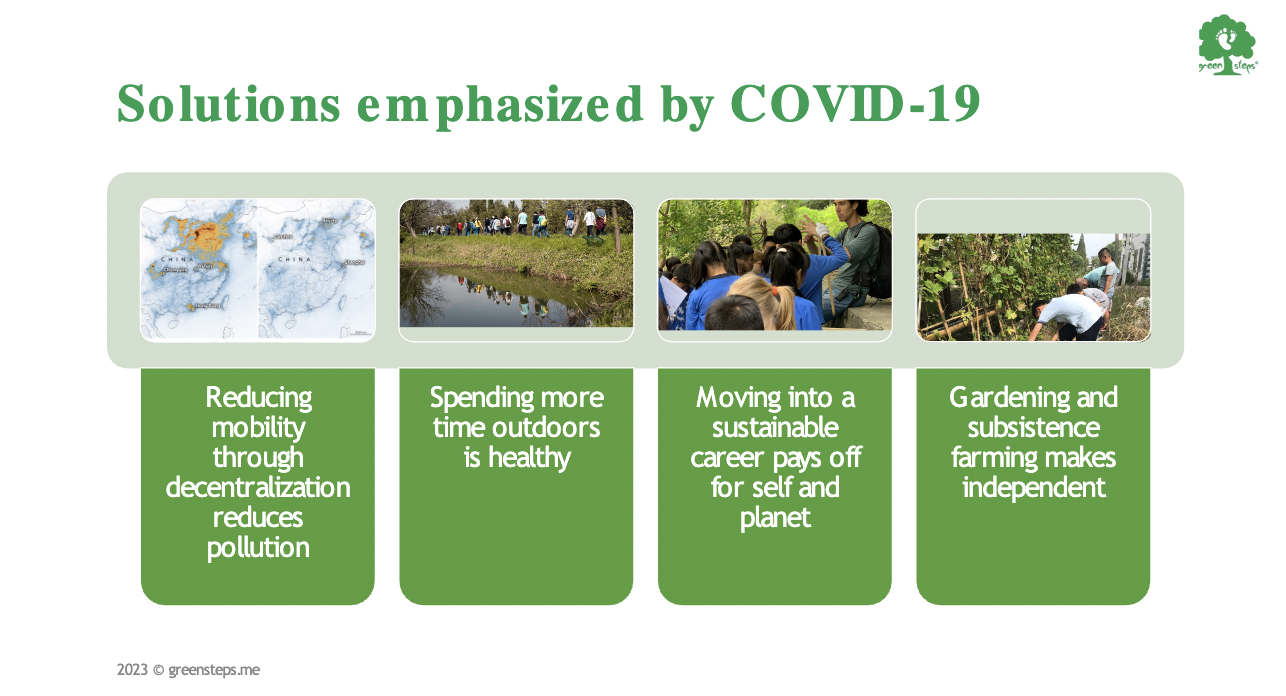

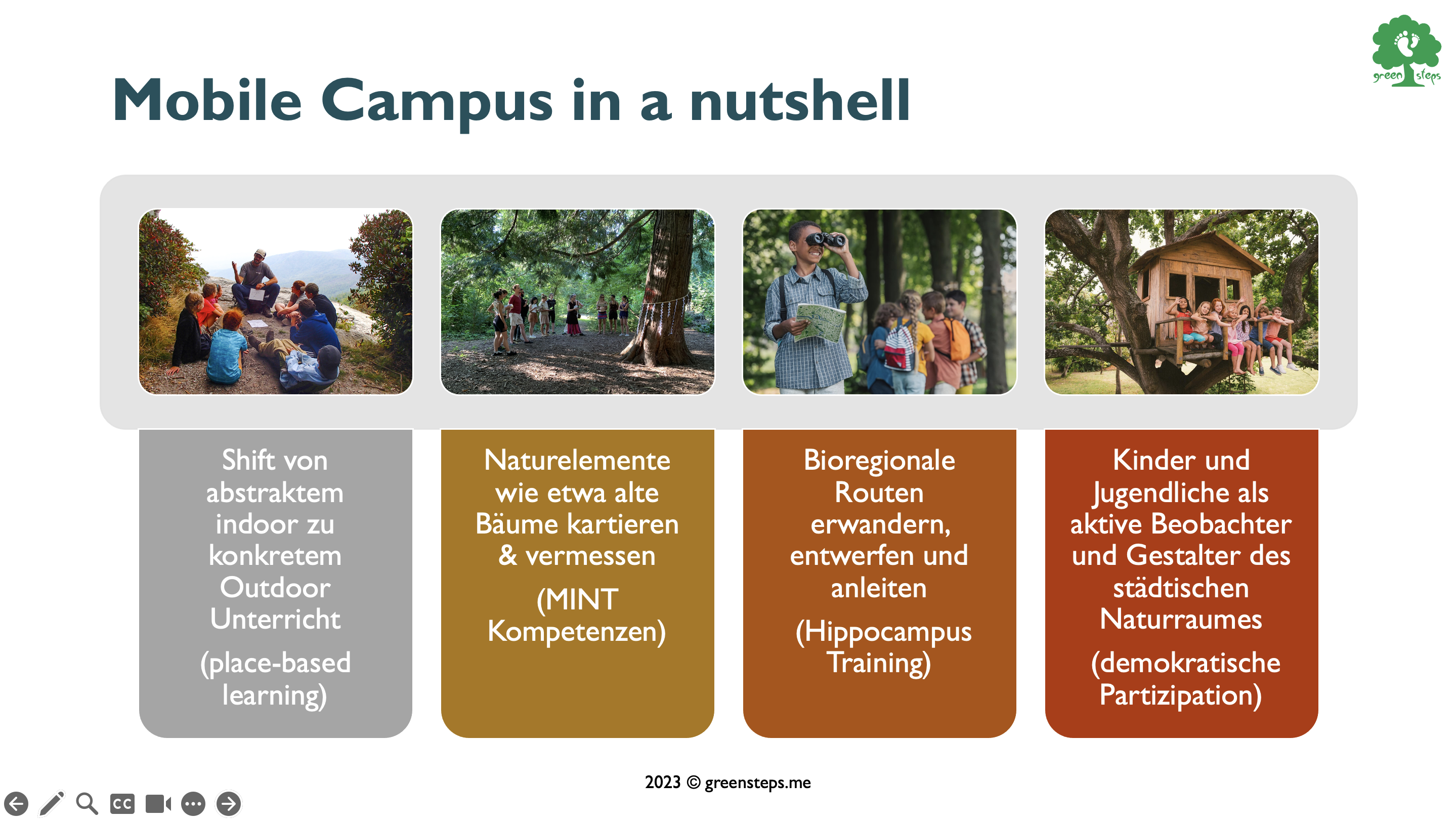

Mobile Campus 4.0 offers a solution to the dilemma faced by schools, students and teachers: the limitation of space by curriculum and liability issues. Experiencing local ecosystems - starting from the school building - must be a key educational goal if we want to best prepare the next generation for the climate crisis and how to address it.

With the support of a customized web-app, exploring, capturing and shaping the extended habitat becomes an adventure. Prepared but dynamically modifiable walking routes along key natural features allow for in-depth familiarization with the habitat. Primary experiences again become the norm, while secondary experiences take a supporting back seat.

Ecological intelligence is fostered through play as participating students measure, describe, map, research, write about, or artistically engage with trees and other natural features. Route development and signposting requires teamwork and trains self-perception and the perception of others.

School open spaces as safety zones

Our fifth and last stop on this insightful day confirms that the reality of urban and rural children in Austria no longer differs drastically, and that Mobile Campus 4.0 will also find application in rural communities. In Aggsbach, a town with 600 inhabitants, the deputy mayor welcomes us to an approximately 1000m2 plot of land about 200m from the elementary school.

Although the elementary school has only 8 pupils, a EUR 45k free space was built in Aggsbach in 2019 as the first project of Familienland GmbH. One wonders why such a small, nature-loving community like Aggsbach, which is located on the Danube in the beautiful Wachau, needs a school open space. The answer is given by two children I meet and ask what they enjoy most here. The answer is again the water pump. "We can drink that, splash with it and play." But why don't you just go to the Danube? I want to know further, "Because our parents won't let us."

School open spaces like the one in Aggsbach show that we no longer allow our children to play freely and thus provide less and less authentic experience of nature. If we take the development of the next generation seriously, then we must take a comprehensive view of the space that children are allowed to develop - beyond the school building and the school garden. We must give them the time to experience this space and the freedom to direct experiences themselves. In the process, things go wrong now and then, no question. But scratches, bumps, scrapes, and a broken arm weigh less than a humanity alienated from nature.

Further reading:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Place-based_education

Handbuch der LReg Oberösterreich, Wege zur Natur im Schulgarten

Richard Louv, Last Child in the Woods

Lia Karsten, It All Used to Be Better? Different Generations on Continuity and Change in Urban Children’s Daily Use of Space

Richard Louv, Engaging children in Nature