Author:

Green Steps

Short summary:

Vienna, 14.10.2022. Sibylle Hamann, Member of Parliament and education spokesperson for the Austrian Green Party, visits with us the exhibition Hot Questions Cold Storage in the Center for Architecture Vienna, one of the oldest and extensive collections on architectural history. An exploration of what architecture and education can do together to solve pressing challenges.

Anne Wübben, architect and youth curator at Vienna's center for architecture (short AZ W) leads through the exhibition and together with Green Steps' co-founder Knut Wimberger unfolds a dialogue on an interdisciplinary subject: the role of the city as an educational space. The museum director Angelika Fitz is pleased about the visit of MP Sybille Hamann and joins us for a meaningful group photo under one of the seven exhibition questions: Who provides for us?

The informative exhibition Hot Questions Cold Storage was curated by Monika Platzer and conceptualized by Angelika Fitz. Seven questions of the present (hot questions) are asked to the Museum Archive (cold storage) in order to obtain urgent answers for our future: Who are we? How does architecture come into being? Who is involved? How do we want to live? Who takes care of us? How do we survive? And why did we make it out of the caves?

Exhibits from the museum archive located in Möllersdorf near Vienna provide the answers. It consists of private collections and gifts from renowned architects and is one of the world's most extensive historical collections of architecture and urban development. Thus, the visitor of the exhibition gains a historical understanding of the demands on urban development and building planning starting from Vienna's early 19th century up to the present time, and gets a good foundation to discuss answers for necessary transformations towards postmodernism.

More than half of humanity lives in cities. In the EU it is more than 75%, in Japan even more than 90%. By 2050, more than 75% of all people will live in cities. The design of the city is therefore of extraordinary relevance and the guiding question of the museum "What is architecture capable of?" is naturally of central relevance. Today, however, the discipline of architecture meets pedagogy. Knut Wimberger is a partner in Green Steps, a nonprofit founded in Shanghai in 2017, and has been managing the European branch since 2020. The dialogue tour will therefore also address the question "What is education capable of?" or "What can education achieve when intertwined with architecture?"

Green Steps won with the project "Big Friendly Giants" in the 2021 Ö1 initiative Fixing the Future and was invited by the museum to showcase its pilot project. The interdisciplinary team mapped over 400 trees aged 100 years or older (aka Big Friendly Giants) on a self-developed app and connected them into experiential routes which present the city as a survival and learning space. The trees function similar to cultural monuments as quasi-permanent landmarks to understand nature as an interconnected system. Green Steps accompanies schools on these routes and helps teachers to build competencies which are believed to be essential in the Anthropocene: systems thinking and ecological empathy.

The dialogue tour starts with Vienna as capitalist city, and shows an installation about soil compressed after surface sealing. Recent studies on the ecological sustainability of urban trees have led the city of Munich to enshrine in law, how large the ground space available to a tree must be: at least 4x6x1.5m, i.e. 36m3 of uncompressed underground living space must be granted to an urban tree.

Knut Wimberger uses the opportunity to point out the value of repeated city walks. The modern city dweller moves 90% between two places only: the adult between home and work, the child and adolescent between home and school. This behavioral reality creates a certain "systems blindness" that is only healed by repeated ecoysystem experiences. One of the pilot project's learning goals is to train people to pay attention to climatic and urban planning changes. For example, to even identify the trees for which surface sealing shortens their lifespan and thus reduces potential ecosystem services, one must constantly study the ecosystem to notice changes. The partially standardized walking routes open up new perspectives in the hometown and make it easier for teachers to meaningfully supplement lessons in the school building with the natural space that surrounds the schools.

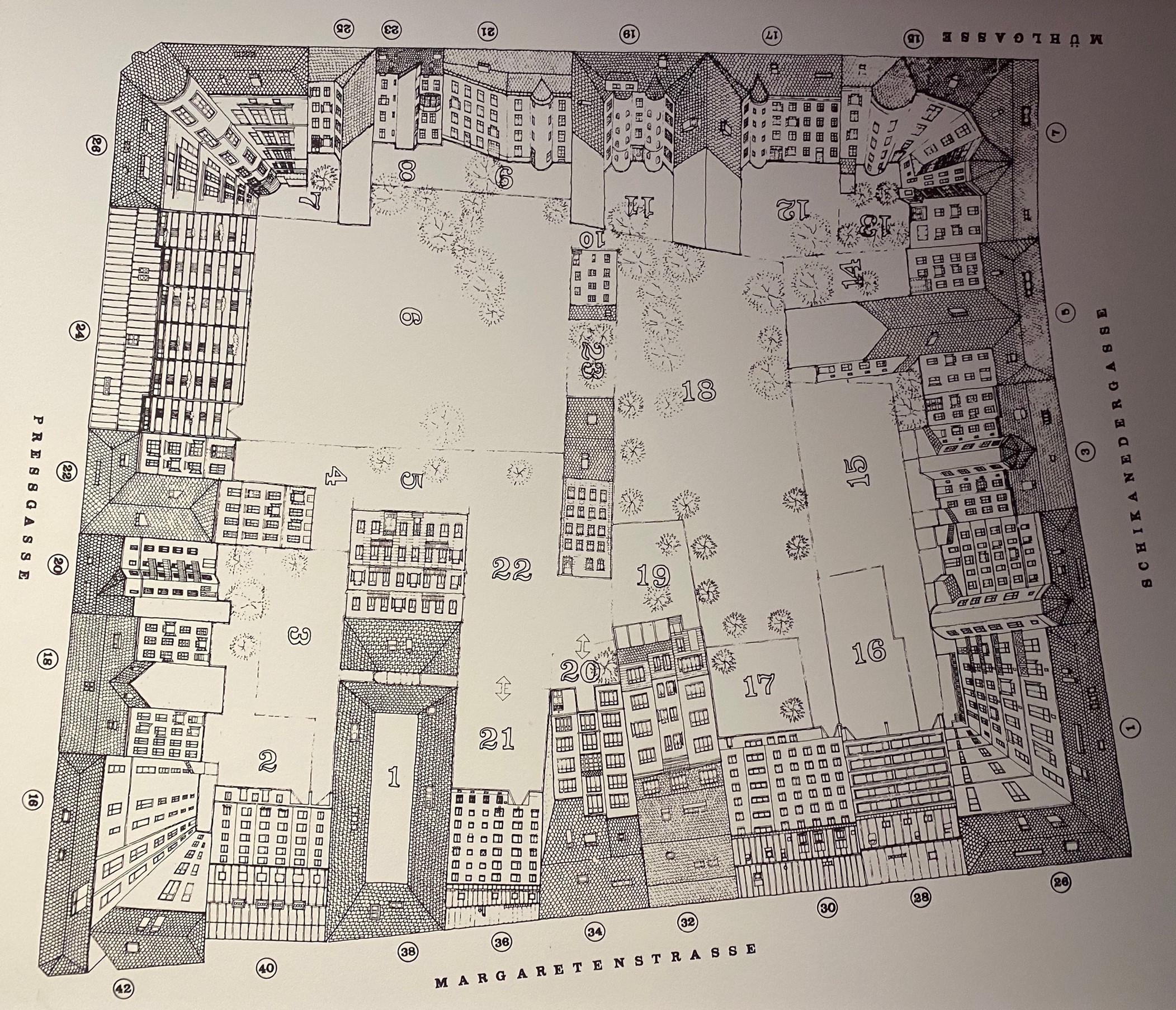

Capitalist Vienna is juxtaposed with the world-renowned social housing of anti-capitalist Vienna. To create housing is undoubtedly one of the tasks of a social city administration, but especially with a view into history, a question arises for the most pressing tasks of the present and the future. What measures must an anti-capitalist city of the 21st century take? Is social housing still sufficient? The site of the Planquadrat in Vienna provides a pioneering answer to this question. The tiny courtyards of two dozen apartment buildings were united in a citizens' movement in the 1970s and have since been managed collectively as a single 5000m2 green space.

The capitalist administrative approach is juxtaposed with an anti-capitalist solution in this project near Vienna's Naschmarkt, illustrated by the original area map. The capitalist handling of property ownership led to unusable inner courtyards separated by high walls, creating "little boxes" loosely based on political activist Malvina Reynolds. The principle of "more for all through sharing" manifested itself as previously unusable spaces were added to a larger common area. An interesting ORF documentary shows the hurdles behind this effort and makes visible that with increasing size of the designed space, the need for social innovation or grassroots democratic participation grows.

With the pilot project Big Friendly Giants, Green Steps tries to take the systemic view of the problem of co-existence to the next level: the focus is no longer on the individual building or apartment block, but on the entire city or the ecosystem in which the city is embedded - and the planet at large. As can be seen in the exhibition Europe's Best Buildings, which is shown simultaneously in another part of the museum, the current field of action of architecture is mostly limited to individual buildings or a group of buildings, while that of environmental education includes buildings as part of the urban learning space. Environmental education takes on a grassroots democratic connotation, as it equips people with the understanding to take responsibility for their own living space and provides them with the skills to participate in decision-making. Is there a more important educational mission in democratic societies facing an ecological and social crisis?

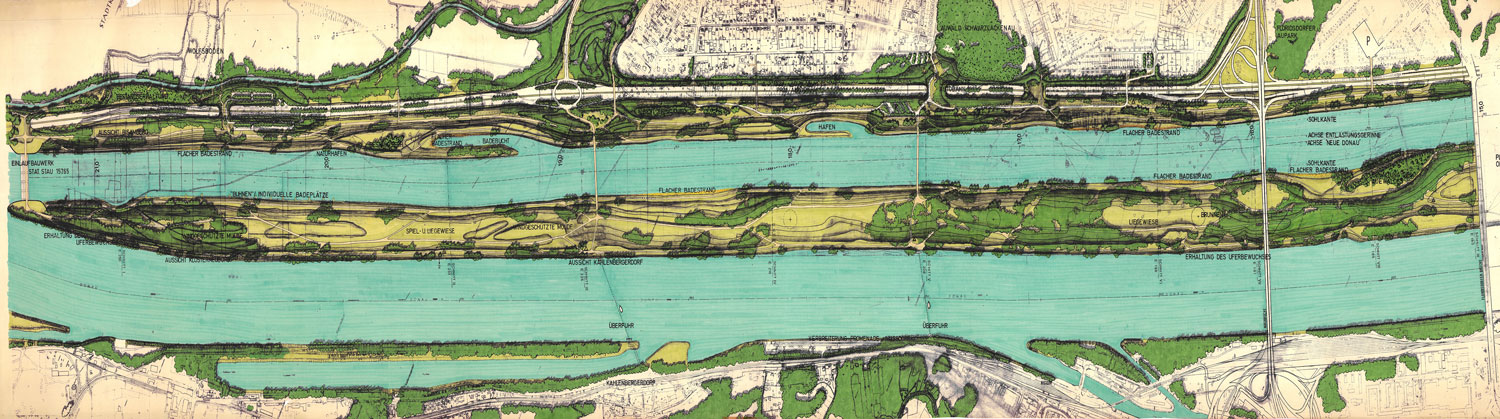

The possibilities of the city administration to create common areas - consciously or unconsciously - are shown in the exhibition by means of the 21km long Danube Island, which was built as flood protection and handed over to the population as recreation area in 1983. In this context, Anne Wübben questions Green Steps' project goal of bringing the somewhat extinct concept of the commons back to life. The Danube Island is however only a public space, but not a commons in the strict sense, as it lacks the institution that manages its ecological carrying capacity. Anthropologist and co-founder of the Deep Ecology movement Gary Snyder defined commons as: "the undivided land that belongs to the members of a local community as a whole."

Cities are commons that have been destroyed and the city dweller loses awareness of the carrying capacity of nature. Commons are experienced spatially and can not be understood in classrooms. Both the capitalist city, which divides ecosystems into small boxes of private property, and the alienation of the sealed city from the undeveloped surrounding countryside make holistic perception increasingly difficult, to the extent that the city dweller loses his "human scale" relationship to nature and thus to the planet as a whole. The question "How do we survive?" emphazises this educational vaccuum, because if we as a society do not understand the carrying capacity of the ecosystems in which we live, it becomes impossible to adapt our actions accordingly.

In connection with the question of survival, environmental education becomes a tool of behavioral architecture: the more fellow citizens understand the carrying capacity of the respective city or district at a young age, the more there will be ideas, on the one hand, to increase this carrying capacity, e.g. through innovative urban farming in previously unthought-of places, and, on the other hand, to refrain from wasting or polluting resources.

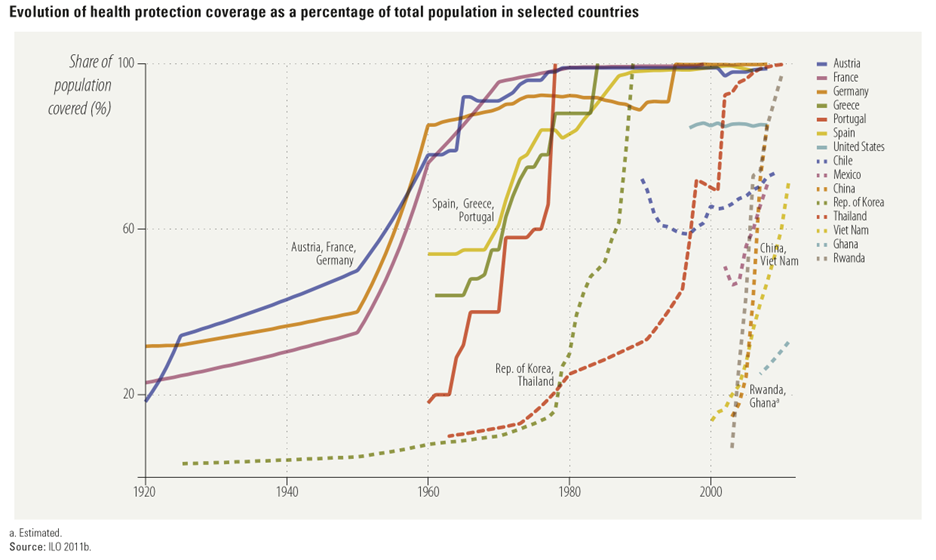

A fourth and final stop in this dialogue tour explains why this systemic perception of the ecosystem is of outstanding educational relevance. In response to the question "Who provides for us?" the exhibition shows the achievements of welfrare systems in the course of early urbanization. The planning focus on hygiene improvement found in architecture already in the second half of the 19th century a tool to create "hard infrastructure" that enabled more and more people to move from the countryside to the city. There, increased life expectancy through social services was a political milestone in the establishment of a "soft infrastructure" that was introduced step by step in the first half of the 20th century.

Under the subtitle "from the cradle to the grave", the exhibition shows plan sketches by Otto Wagner for crematoria and public toilets, as well as models of schools and kindergartens. Austria, and above all its capital Vienna, played a pioneering role in terms of both hard and soft infrastructure, which was only interrupted by World War II. As is widely known, however, Vienna has for some years been leading international rankings on the quality of life in large cities, reflecting to some extent both the natural infrastructure as well as political decisions on hard and soft infrastructure. The graph below illustrates the early introduction of comprehensive health insurance between 1920 and 1980 in several countries.

The prosperity of cities and the better provision of education and health care facilities made cities preferred places to live during the Industrial Revolution. However, the climate crisis and COVID-19 show that large urban areas can quickly become death zones when unexpected pathogens paralyze hospitals or logistical problems interrupt the supply of food. Understanding the city habitat as an ecosystem that should also function independently of the hinterland and creating urban commons to maintain food supplies are issues we cannot address early enough. Environmental education thus becomes survival education and should be added to the curriculum sooner rather than later.

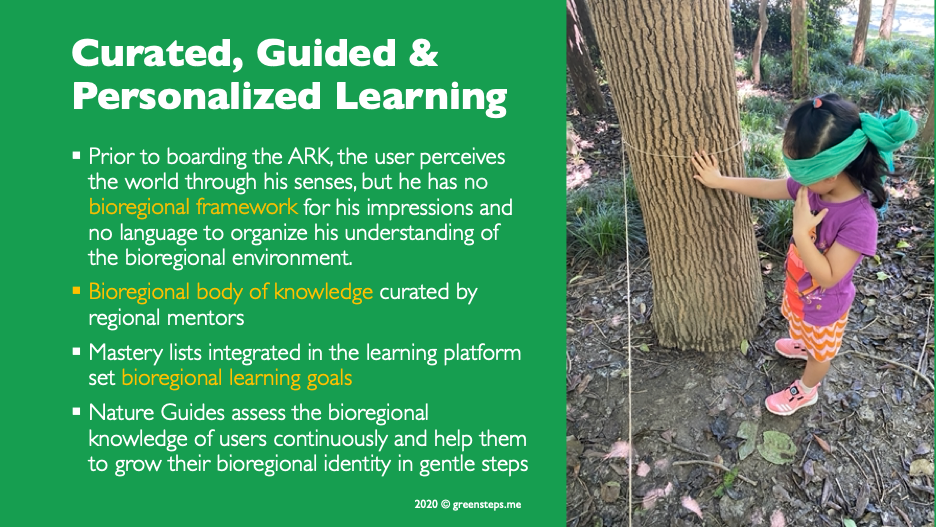

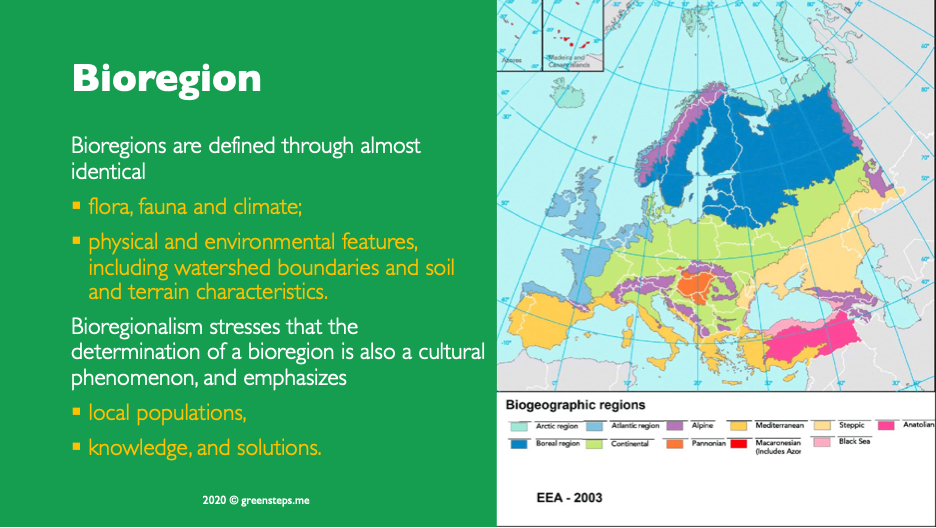

The commons is a strange and elegant social institution within which people once lived free political lives while moving through natural systems. The commons is a level of organization in human society that includes the non-human, such as ancient trees, leading to a holistic perception of nature. The level above the local commons is the bioregion. Understanding the commons and its role within a larger regional culture is another step toward integrating ecology and economy, which can be learned through play in projects like that of Green Steps. Both the pilot project and the app developed for it have been available for school trials since the summer.

The question "Who provides for us?" takes on another meaning in terms of social welfare, because without doubt the basis for any kind of infrastructure is Mother Nature herself. Green Steps pursues the understanding of this renewed dimensional change by learning about bioregional flora and fauna, which is perceived, discussed and recorded in "nature journals" on the routes. Environmental educators and teachers can use the intuitive app to visualize the learning progress of their students by awarding species and concrete specimens such as natural monuments as collectible cards on the student's profile after real world encounter. Repeated hikes result in a measurable and holistic learning progress for each student, which is expressed in a so-called bioregional identity.

Environmental education thus becomes measurable and comparable for the first time. More importantly, however, through the indirect learning goal of creating bioregional identities, applied integration work is being done. While cultures often painfully divide, the shared experience of the natural space helps to perceive it on the level of the commons as an ecosystem worthy of protection, and stewardship of our natural habitat emerges as a common ground. At the level of the bioregion, an understanding grows that we share our flora and fauna within climatic zones across political boundaries, and within these territories created by the laws of nature, we are inhabitants of a single oversized ecosystem: Earth.

Psychology has coined the term overview effect for this cognitive change of perception, because it has been observed in all astronauts who have seen the Earth from outer orbit. If they had flown into space as citizens of a nation state, they came back as citizens of the earth who had become emphatically aware of their responsibility towards this habitat. The work of Green Steps aims at the same understanding on this higher level, but without having to catapult the whole of humanity into space.

Further reading:

- Mag. Sibylle Hamann

- Exhibition Hot Questions Cold Storage

- Introduction to the exhibition youtube

- Ö1 Repair the future

- Guide Urban Trees Center for Urban Nature and Climate Adaptation

- Garden courtyard association Planquadrat

- Exhibition Europe’s Best Buildings

- Donau Island

- Gary Snyder: The Practice of the Wild

- Malvina Reynolds: Little Boxes

- Deep Ecology

- Knut Wimberger: Cities and their evolutionary purpose as learning spaces

- How our property laws impact climate change

- Our World in Data: health investment and outcome

- Overview Effect